The River Strikes Back: Climate Warnings and Anti-Encroachment Lessons from Swat

Rivers remember! They remember the paths they once carved through valleys, the rhythms of monsoon rain, and the whispers of melting snow. In the Swat Valley, that memory is stored not in folklore alone but in data, in streamflow records, glacial melt curves, and hydrological models that show how climate change is rewriting the story of Swat River.

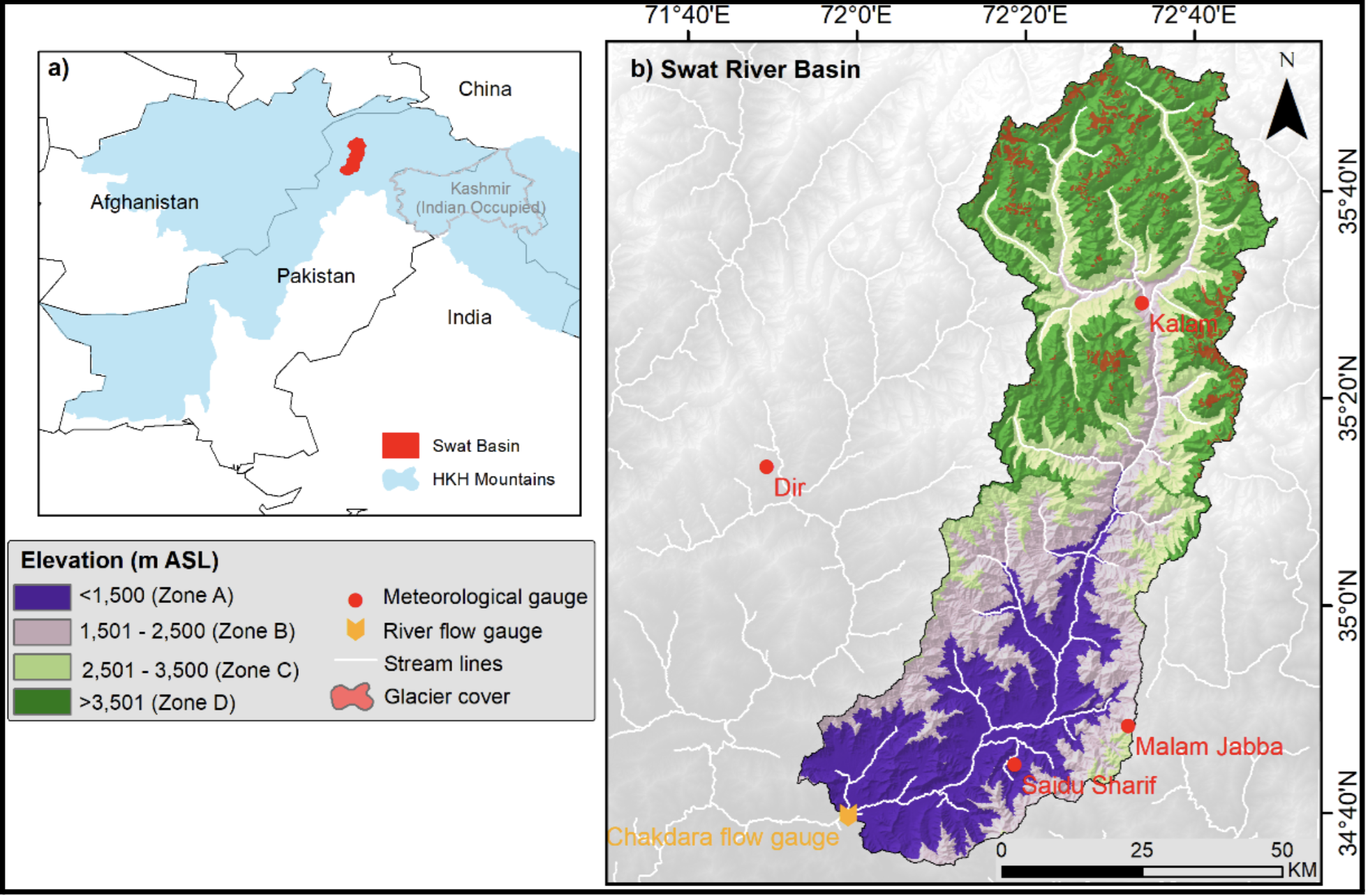

The Swat River is located in the Hindu Kush region of northern Pakistan, flowing through the high-altitude valleys of Kalam, Bahrain, and Mingora before joining the Panjkora and ultimately the Kabul River.

Swat River Basin (Source: Romana Jamshed et al., 2025)

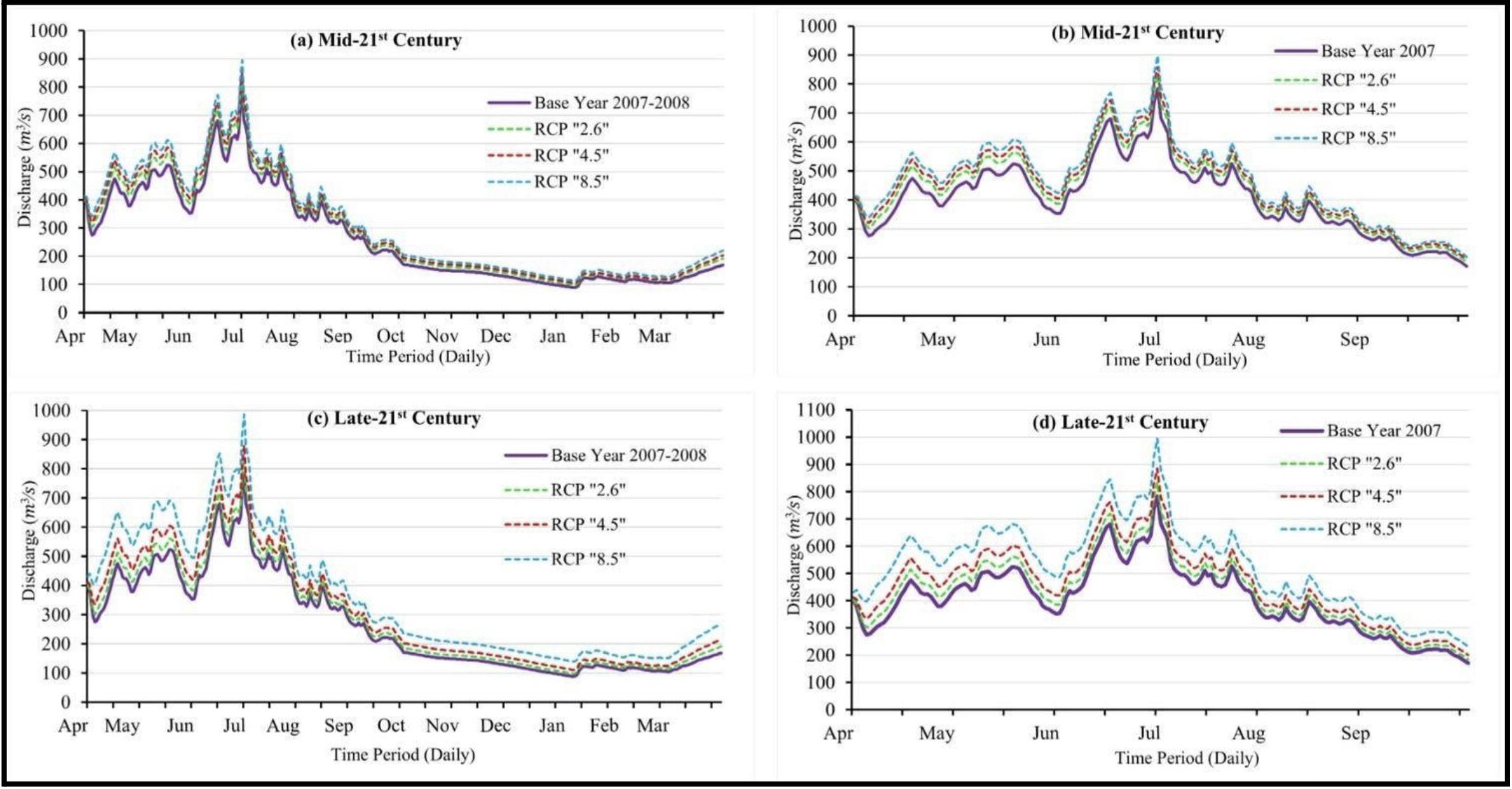

Recent modelling of the Swat River Basin shows just how quickly this memory is being altered by a warming climate. Using a snowmelt–runoff model for this snow and glacier-fed catchment, researchers project that mean annual flows could increase by roughly 8–18% by mid-century and 7–34% by the end of the century, with about a 6–7% rise in flows for every 1°C increase in temperature (Romana Jamshed et al., 2025). In practical terms, this means earlier and higher flow peaks, more energetic floods, and greater pressure on any settlements and structures forced into the active floodplain (Romana Jamshed et al., 2025).

Climate change Scenarios for Swat River Basin (Romana Jamshed et al., 2025)

When a Picnic Turned Into a Flood Tragedy

The most haunting reminder of the power of the river came in a monsoon in 2025, when tourists who had travelled to Swat for a picnic were caught in a sudden surge of water. The Swat River did not strike that day out of rage, it struck because we refused to listen. The tragedy that claimed 12 members of the same tourist family from Sialkot and Daska who had come to Swat (River Swat) for a peaceful weekend picnic was not a random misfortune. It was the predictable outcome of unchecked climate risks, public unawareness, illegal riverside development, and the absence of early-warning culture. According to rescue officials, 18 members of the group were swept away when a sudden flash flood surged through the river, leaving bystanders on the opposite bank screaming and helpless as the family clung to a shrinking gravel island before being pulled away one by one (Dawn News, 2025).

Swat River tragedy (Source: Pakistan Television)

The teams of the rescue department (Rescue 1122) searched the river for days. They confirmed that 12 bodies were recovered, including that of a young child found downstream in Charsadda (Rescue 1122, 2025). Officials from the Provincial Disaster Management Authority (PDMA) later reported that at least 19 people were killed and six injured across Khyber Pakhtunkhwa during the same wave of flash floods and landslides triggered by intense, localized rainfall (PDMA 2025). Many of these floods originated far upstream, sometimes more than 100 km away, a common hydrological pattern in mountainous terrain where heavy rain funnels rapidly into steep valleys.

What makes this tragedy even more devastating is that no public warning system existed to inform tourists that the river could rise violently without a single drop of rain at the picnic site. The Swat River is fed by the Ushu and Gabral tributaries in Kalam, as well as glacial lakes such as Mahodand, Kundol, Shahi Bagh, Spin Khwar, and Indrap—waters that can surge suddenly during heavy rainfall or rapid temperature rise (Local Hydrology Reports, 2024). Phenomena like Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs) and cloudbursts are also becoming more frequent and destructive as the climate warms (UNDP 2023; ICIMOD 2024).

Despite this escalating danger, no government institution or department has yet published and implemented a climate change inclusive analysis of recurring floods of Swat which takes public behavior into consideration. As experts note, these are not “natural disasters” but disasters shaped by human neglect and the absence of climate adaptation capacity (World Bank Climate Risk Profile 2023).

The Billion Tree Tsunami, launched in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in 2014, was a large-scale reforestation campaign with the objective to restore forests and reduce environmental degradation. However it was well-intentioned but insufficient . Reforestation alone cannot stop flash floods without parallel investments in riverbank reinforcement, catchment management, early-warning systems, and real-time rainfall monitoring. Swat, once dubbed as the Switzerland of the East because of its snow-capped peaks, pine-covered slopes, and open meadows, has long been its pride. But years of conflict, repeated floods, and economic hardship have pushed many residents to exploit the natural resources of the valley for survival. In this struggle, the long-term health of the landscape has often been overlooked. In fact, rampant illegal logging and deforestation in upper Swat continue to accelerate runoff, worsen soil instability, and increase landslide risk (WWF Pakistan 2022). Experts claim that 30% to 40% of trees in various regions of Swat have already been cut down, and those involved in the process aim to raise this to 70% of trees in the district.

Rampant Deforestation in district Swat (Source: The Friday Times)

Compounding the crisis was the failure of the media. While outlets were quick to broadcast heartbreaking footage of the drowning victims, not a single investigative or climate-risk report had warned in advance about rising flood vulnerability of river swat, upstream rainfall surges, illegal riverbank construction, or the absence of emergency alerts (Media Monitoring Review, 2025). The national conversation only began after lives were lost, when it was too late to save the victims.

The uncomfortable truth and hope

Until awareness becomes preventive rather than reactive, Swat and Pakistan as a whole will continue to face tragedies that could have been avoided.

As the Swat tragedy forced the province to confront uncomfortable truths, the state has finally begun acting where it long hesitated. In July, a grand anti-encroachment operation was launched in Bahrain Tehsil on the directives of the Peshawar High Court, reclaiming 4.5 kanals of state land from illegal construction (APP, 2025). This was followed by a coordinated push in Kalam from 6 to 8 November 2025, where the Irrigation Department (Swat Irrigation Division-II, Matta), district administration, and revenue officials completed a full demarcation of high-water limits. Encroachments were marked on site, and after community Jirgas, controlled demolition began on a multi-story structure built directly in the path of the river (Irrigation Dept. Swat, 2025).

Anti-encroachment operation in Bahrain, Swat (Associated Press of Pakistan)

These operations mark one of the most assertive government responses in years. Led by officials including DG Upper Swat Development Authority, DC, AC, and AAC, the campaign involved multiple departments: Rescue 1122, Irrigation, Police, Levies and Revenue working together for once, not after a disaster, but to prevent the next one.

Anti-encroachment operations are not about punishing shopkeepers or hotel owners, but are about restoring the physical space the river needs to pass safely. Without removing illegal construction choking the Swat River, even the best hydrological modelling, climate research, or early-warning systems cannot save lives. But selective enforcement, political interference, or poorly communicated demolitions can undermine public trust and provoke resistance. That is why the current approach combining court orders, technical demarcation, administrative enforcement, and community Jirga is a positive shift.

The true measure of success will be persistence, not headlines…..

Will these operations continue uniformly across Bahrain, Mingora, Kalam, and lower Swat?

Will future construction be stopped before it begins in the riverbed?

Will the high-water limits mapped in 2025 become binding zoning laws?

If the government sustains this momentum and pairs it with public education, river safety culture, scientific flood mapping, and long-term catchment management, then Swat can avoid repeating the scenes that shocked the nation this year. At the same time, progress will only be possible if all stakeholders take responsibility and public institutions, local communities, NGOs, and especially those in positions of power who have influenced or allowed encroachment for years. Without collective cooperation, transparent enforcement, and a serious commitment to public awareness and education, sustainable change will remain impossible. If these responsibilities are ignored, we will continue to mourn lives lost to disasters that were never natural, but entirely neglected.

For the first time in years, the riverbank is being cleared. The question now is whether this effort is merely a reaction to tragedy, or the beginning of a new relationship between the people of Swat and the river that has shaped their valley for centuries. Once again, the choice is ours and the consequences will be too.

References

Associated Press of Pakistan. (2025). Anti-encroachment operation in Bahrain, Swat. Government of Pakistan News Agency (APP).

Dawn News. (2025). Flash floods in Swat: 12 bodies recovered, several still missing. Dawn Media Group.

ICIMOD. (2024). Glacial lake outburst floods and climate risks in the Hindu Kush Himalaya. International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development.

Irrigation Department Swat. (2025). Demarcation of high-water limits and anti-encroachment drive in Kalam (6–8 November 2025). Swat Irrigation Division-II, Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

Jamshed, R., Naeem, E., Tahir, A. A., Irshad, M., Qaisar, F.-u.-R., Arifeen, A., & Muhammad, S. (2025). Modeling snowmelt-driven streamflow dynamics in a Himalayan Basin under climate warming scenarios. PLOS Climate, 4(10), e0000739.

Local Hydrology Reports. (2024). Hydrological assessment of upper Swat tributaries. Provincial Irrigation Department, Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

Media Monitoring Review. (2025). Coverage gaps in climate-risk reporting across Pakistani media. Center for Media Literacy Pakistan.

PDMA Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. (2025). Flash flood situation report and rainfall impact update. Provincial Disaster Management Authority.

Rescue 1122 Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. (2025). Flash flood response and recovery operations in Swat and Charsadda. Emergency Rescue Service Report.

UNDP Pakistan. (2023). Climate resilience, GLOF risks, and disaster preparedness in northern Pakistan. United Nations Development Programme.

World Bank. (2023). Climate Risk Profile: Pakistan. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank Group.

WWF Pakistan. (2022). Forest loss and watershed degradation in Swat Valley. World Wide Fund for Nature Pakistan.

The Friday Times. (2023). Illegal logging and deforestation trends in district Swat. The Friday Times Editorial Report.

Written by Muhammad Ishaq

MSc Water Resources Engineering, UET Peshawar | Grenoble INP – Graduate School of Energy, Water and Environment (ENSE3), France | Water Restrictions modelling with Électricité de France (EDF)